I have to stop buying things just because I think they’re funny. A somewhat recent example: at the end of June, I purchased a pastel blue baby tee from Ross for $10 with the words “Brooklyn Baby” screen-printed on it. In my head, I was already three layers of irony beyond the shirt:

I was at Ross in the first place because someone on TikTok told me to “run, don’t walk” there for the baby tee selection, including Peanuts, Budweiser, and generic “Los Angeles” merch. Somewhere between tourist shops, Urban Outfitters, and Brandy Melville, allegiance to a given place has become separated from wearing crop tops or sweatshirts with that place name on them. (My roommate and I recently had a discussion about whether it would be more embarrassing for her or for me, a Californian, to wear a Brandy Melville item with “BAY AREA” written on it.) Surely a real Brooklyn baby wouldn’t need a shirt to announce it, and I was running and not walking to a Ross in Missouri to pretend to be a Brooklyn baby.

“Brooklyn Baby” is famously—or at least, famously to me—a song title from Lana Del Rey’s 2014 album Ultraviolence. There’s a certain sense of ambivalence about the clothes at discount stores like Ross—sometimes they’re on trend or good quality or a solid bargain for the brand, but they usually aren’t. Was this shirt a covert piece of merchandise? When Brandy Melville sells a shirt with Jesus on it, you have to assume they’re somewhat in on the joke.

I’m typically not one of those people who dresses in an especially coquettish or “Lana Del Rey vinyl” manner. I dabble in that kind of femininity, maybe, but not in a way that implies I want to have a torrid affair with an older man in the mafia who dies in a violent encounter and leaves me to mourn our powerful yet doomed love. Something about Lana’s multiplicity—the Waffle House shifts, the Grammys dress from Dillard’s, the recent marriage to an alligator tour guide from Louisiana—makes people especially eager to pin her down to one kind of Americana aesthetic. The “Brooklyn Baby” shirt is sort of a hard launch of Lanaism, then, compared to the privacy of listening to “Fucked My Way Up To The Top” in my earbuds.

With each step, the sense of insider enjoyment gets smaller and smaller until I’m left thinking about how clever I am. Somehow, this is what it means for me to dress for myself—to begin with the norms of what (I imagine) clothing signifies, and to comply with or undermine these signifiers in a way that makes me happy. On Thursdays, when I have my thesis seminar, I try to dress extra studious, or in a way that typically signals studiousness (glasses; items characteristic of school uniforms; a type of frumpiness, almost). I dress so varied with the hope that my outfits in aggregate will reveal some unchanging essence within me. I want to be a person with range, someone who can pull off all these different styles at once. Buying clothing is less a decision about what kind of person I currently am and more about what kind of person I want to be. I wanted to be someone who owns a “Brooklyn Baby” shirt, and now I am.

Isabel Cristo opens her essay “On Getting Dressed” for The Paris Review by declaring, “When I get dressed, I become a philosopher-king,” and this is how it feels to dress with any kind of aesthetic cohesion. On the Fourth of July, I wore the “Brooklyn Baby” shirt as a sort of Lana tribute with big boots and a blue lace slip skirt I’d found at the Goodwill bins. I wondered all day whether this kind of ironic patriotism—the color scheme and the text on my shirt—was more ironic or more patriotic. A girl inside the Free People store at the mall told me she liked my outfit. There’s a private satisfaction in being mistaken for the type of person who would wear a “Brooklyn Baby” baby tee with a vintage slip skirt and boots to shop at the mall Free People, even though that’s exactly what I was doing. I’m secretly very pleased by the notion that the inferences someone might make about the rest of my life could be wrong.

The shirt’s next outing was on a Saturday morning to the local Goodwill and the grocery store. This time, I wore it with my platform Doc Martens and low-rise bootcut Express jeans that I’d worried were too Y2K baddie for me but had purchased anyway because they were only three dollars. The silhouette in general felt too obviously trendy, verging on inauthentic, but the disconnect between myself and my outfit made me want to give it a try. While I flipped through the rack of skirts, a ten-ish year old girl ran past me and said, “Slay queen, you’re so pretty!” By the time I realized she was talking to me, she was gone. I only registered the compliment after thinking about how far these concepts of “slaying” and “queens” have traveled. The baby tee with the jeans signified competence and sass at the same time, like a babysitter or an older sister, and I wondered if she’d identified either of those qualities in me—the eternal Lizzie McGuire archetype.

Later, I was standing by the mirror at the end of an aisle and considering a gray North Face puffer jacket when an older man walked by and said, “You have to get that.” I told him I was still on the fence about it, and he replied, “It’s so you, especially with the Docs.” Then he headed to the checkout line, and I smiled and said something as a parting comment, but this exchange really vexed me. A stranger believed himself to have seen into my inner core and assessed what might be “so me.” I had to revise: it was fine for people to make inferences about me, as long as they didn’t say them out loud. Maybe I didn’t actually want to be knowable, or ostensibly knowable in the way my appearance made me seem to him. (The babysitter thing was more appealing.) And I did want the jacket, but because I liked how it was similar to the North Face puffer jackets seemingly every girl in the UK owned, and because I’ve always hated puffer jackets that are too thin. This is what the buzzword of “personal style” is supposed to indicate: my fashion experience and knowledge and preferences, sifted through and established over a lifetime.

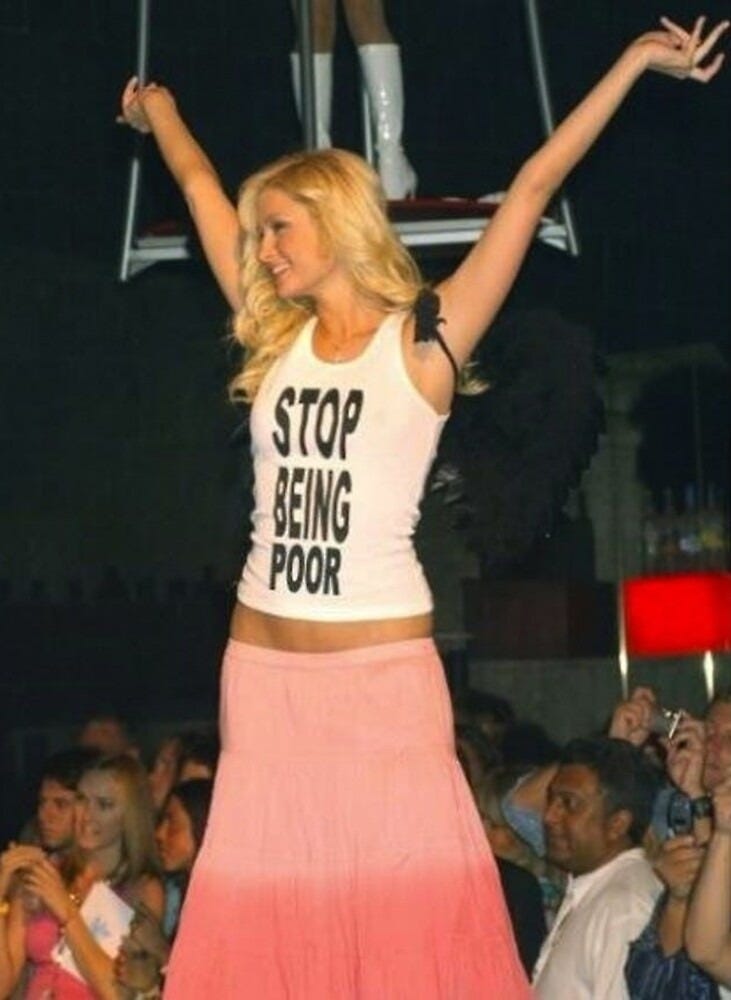

Surely that man had never heard of the Lana Del Rey song, but there was something else he was grasping onto. “Brooklyn Baby” is a pastiche, opening with references to “the freedom land of the seventies” and jumping between references to Lou Reed, Beat poets, and jazz. Contemporary Y2K style isn’t authentic to the 2000s—it’s a combination of the McBling aesthetic, that photoshopped image of Paris Hilton wearing a tank top that says “STOP BEING POOR,” and scans of Delia’s catalogues that continually float around Pinterest. Even Y2K itself as a pseudo-apocalyptic moment is more emblematic of the nineties than the 2000s; people thought the world would end when the twenty-first century started, and then it didn’t. Lana opens the song, after all, with “They say I’m too young to love you”—she doesn’t know what the fuck she’s talking about, either.

Fundamentally, “Brooklyn Baby” is a song about how much better other art is. The song begins as a pastiche of hipster nostalgia, with “a neutral practice of such mimicry” that Frederic Jameson identifies as key to parody in Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. However, somewhat paradoxically, the “satiric impulse” of parody that distinguishes it from pastiche becomes apparent through the lyrics’ lack of anything new or especially interesting. Lana characterizes the temperamental—or generational—differences between her and her older boyfriend through a series of basic similes and metaphors: “I think we’re like fire and water / I think we’re like the wind and sea / You’re burning up, I’m cooling down / You’re up, I’m down / You’re blind, I see.” The sound of the song itself is negligible. It’s about owning the right records and appreciating the Beats and being able to “play most anything” when prompted. She declares that she’s “churnin’ out novels” alongside her music, but when has “churning” ever implied quality?

The image Lana evokes of hipsterism by “talkin’ bout my generation” on the song’s bridge is vague and empty. There’s nothing unique, except maybe her tendency to “get high on hydroponic weed.” (Halsey’s 2015 song “New Americana,” a second alt-pop attempt at a millennial anthem, identifies being “high on legal marijuana” as a generational characteristic, too.) Lana sings, “If you don’t like it, you can leave it, leave it, baby,” but what’s not to like? Everything she identifies in the song has been canonized already, and her churned-out novels and the song itself are seemingly the only new art she has to show for it. “The hipster moment did not produce artists, but tattoo artists,” Mark Greif writes in “What Was the Hipster?”—or, like Lana’s narrator, cover artists who sing Lou Reed songs. Of course, Greif’s piece eulogizing the hipster movement was published in October 2010, nearly four years before “Brooklyn Baby” was released. I was a preteen when all this happened, so I’m a tattoo artist, too.